This article, and all my work, is made possible by the incredible generosity of my paid subscribers. Your support is particularly important for longer projects such as The Genre Genealogy Series, which I intend to continue offering for free to everyone.

If you enjoy my writing and would like to support me in continuing to produce in-depth content, consider joining our community as a paid subscriber. You'll unlock an exclusive weekly essay, including my new series Short Story Dissections!

Prefer to offer one-time support? I have a ‘Buy Me A Coffee’ site here.

Welcome, welcome, welcome,

This week at The Ink-Stained Desk, we’ll be exploring an extraordinary meteorological event, its global impact, and how a rain-soaked holiday in Switzerland gave birth to literary legends.

Ever imagine that summer just didn’t happen? A year where the sky was always grey, crops failed, and there was this weird chill in the air! This isn’t a scene from a gothic novel, or the latest Hollywood disaster movie, but a real event that took place in 1816, infamously known as ‘The Year Without a Summer’. This wild weather event had huge and far-reaching consequences, disrupting agriculture, sparking social unrest, and, perhaps most fascinatingly for fantasy and horror readers (—and I would hope readers in general), setting the stage for one of the most enduring works of horror in literary history: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

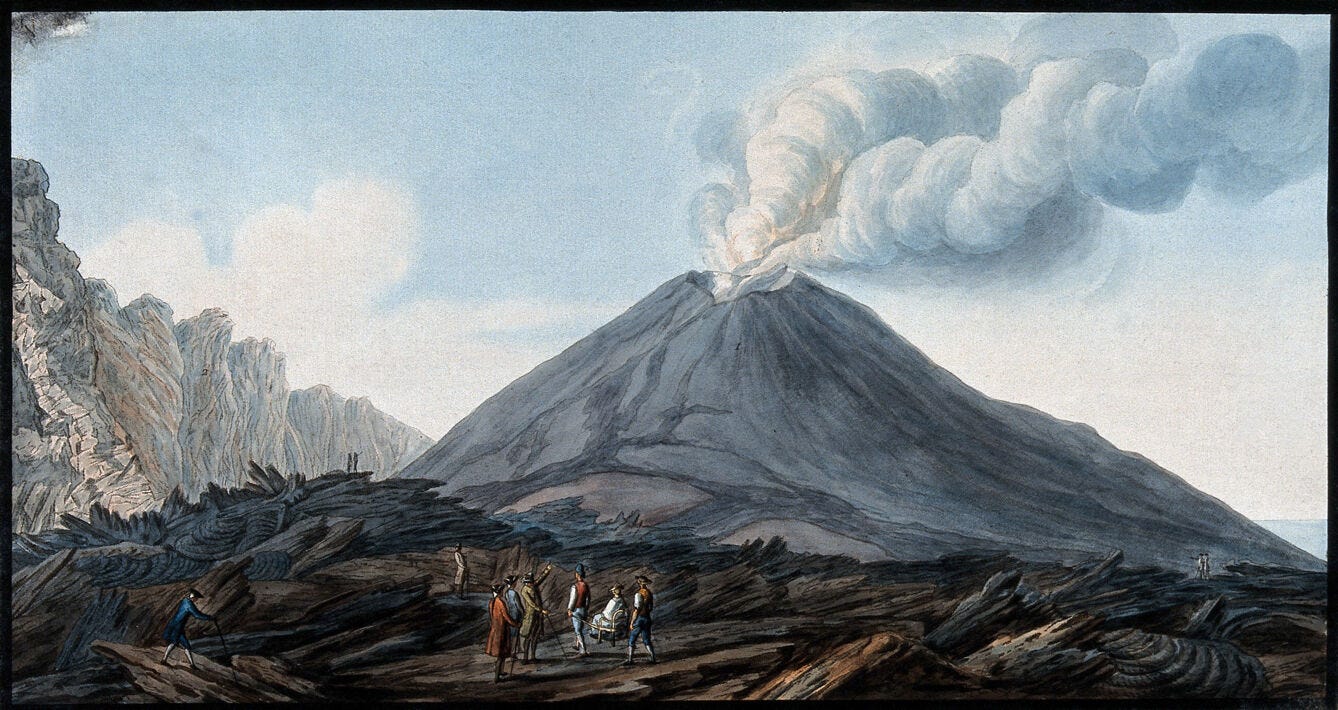

This wasn’t just some strange, unexplainable local weather; it was a global disaster with quite a dramatic cause. In April 1815, Mount Tambora in Indonesia erupted in one of the most massive volcanic events ever recorded. This giant blast shot tons of ash, dust, and sulphur dioxide up into Earth’s atmosphere, forming a huge cloudy blanket that wrapped around the whole world.

This atmospheric ‘sunshade’ (—technically called a ‘stratospheric aerosol veil’) circles the entire globe, preventing the sun from reaching Earth. The result? A massive drop in global temperatures, especially noticeable in the north. Europe and North America had an unusually cold spring, then a summer of non-stop rain, widespread frosts, and even snow in June and July. Crops died, harvests were a bust, and food shortages got really serious, leading to widespread famine and intense social and economic chaos. It was devastating.

Villa Diodati.

It was against this backdrop of persistent gloom and torrential rain that a very exciting literary gathering occurred. In the summer of 1816, a group of prominent literary figures found themselves sequestered indoors at Villa Diodati on the shores of Lake Geneva in Switzerland.

The company included—

Lord Byron: Famous and infamous poet in equal measure. He was renting the villa and played the charming, if sometimes intense, host.

Percy Bysshe Shelley: A radical poet and philosopher, and a good friend of Byron. He was at the villa after running off with his future wife, Mary Godwin.

Mary Godwin (later Mary Shelley): Just 18 years old. Her relationship with the already-married Percy Shelley had caused a lot of gossip!

John Polidori: Byron’s personal doctor, but he was also a writer.

Claire Clairmont: Mary's stepsister and a past lover of Byron’s. (—which you can imagine caused a bit of tension!)

Confined by the incessant downpours, the group amused themselves by reading German ghost stories. It was apparently Byron who proposed the challenge: each person should write their own supernatural tale. What began as a simple parlour game, fueled by boredom and the oppressive atmosphere, soon transcended from mere entertainment into something that would change the literary world.

The Birth of Two Literary Legends.

The outcomes of this amiable competition resonated through subsequent centuries, giving rise to two foundational texts of modern horror.

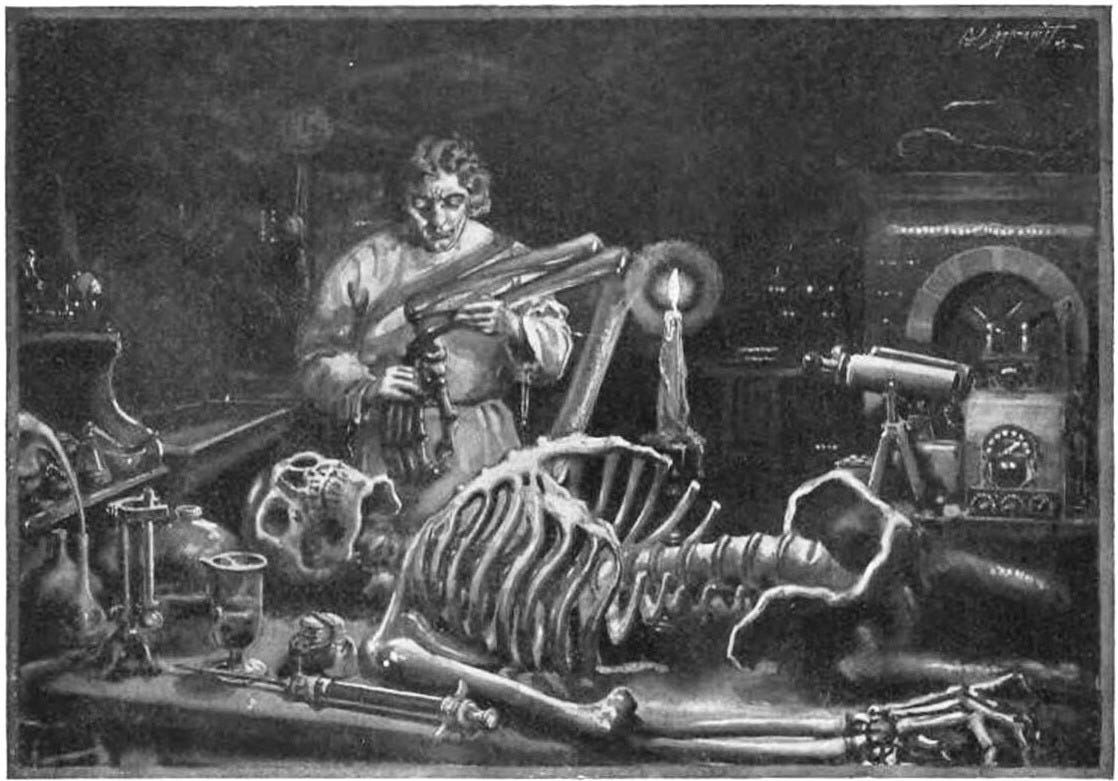

Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus: Mary Godwin initially encountered difficulty in conceiving an idea for the competition. However, a discussion between Byron and Percy Shelley about the nature of life and galvanism (—the generation of electric current through chemical reactions), sparked the terrifying vision, often referred to in texts about Mary Shelley as a ‘waking dream’ of a pallid student kneeling beside the composite being he had assembled, a ‘hideous phantasm of a man’ brought to animation.. This haunting image became the genesis of Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, a novel that profoundly explores the moral and ethical responsibilities inherent in creation.

To explore the historical and folkloric lineage of ‘artificial beings’, and trace their portrayal in literature, please consider reading this week’s paid subscriber essay.

The Vampyre: John Polidori was similarly inspired during his stay at Villa Diodati. Although Byron’s concept for a vampire narrative featuring Augustus Darvell did not reach fruition through his own pen, Polidori adopted the premise and developed it. He authored ‘The Vampyre’, a short story featuring the aristocratic and predatory character of Lord Ruthven. This figure became the archetype for the modern literary vampire—a charismatic, seductive aristocrat who preys upon society, a considerable departure from the grotesque creatures of folklore. Notably, this narrative predated Bram Stoker’s Dracula by over 70 years and established the groundwork for the vampire genre as it is recognised today.

To read more about the vampire myth and its evolution, including Polidori’s story, please click through to last month’s free essay:

Darkness: While Byron’s direct contribution to the ghost story challenge did not fully materialise into a lengthy prose narrative, he did write the poem, ‘Darkness’, in July 1816, during the same period of oppressive weather and intellectual exchange at Villa Diodati. This poem vividly describes a post-apocalyptic world plunged into eternal night and famine, a clear reflection of the extreme climatic conditions of the ‘Year Without a Summer’. It is a powerful and significant work of poetry born from the same dark inspiration. (— I completed one of my major undergrad assignments on this poem, and it has subsequently become my favourite from Lord Byron. It is dark and… let’s just say a little depressing and doesn’t give a whole lot of hope, but if you haven’t read it, please do!)

The gloomy weather and the sense of isolation undoubtedly contributed to the dark and introspective nature of the stories conceived during that fateful summer. The ‘year without a summer’ thus inadvertently provided the perfect crucible for the birth of classic gothic literature.

Legacy of the Dark Summer.

The meteorological anomaly of 1816 eventually passed, but its effects reverberated for years. The human cost in terms of famine and disease was immense, and the economic impact was global. Yet, from this period of darkness emerged works of literature that continue to captivate audiences centuries later (—this gives me pause to wonder about the literature that is being composed in the present time).

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein remains a cornerstone of science fiction and horror, exploring profound themes of creation, responsibility, and humanity. Polidori’s ‘The Vampyre’, though lesser known today, was instrumental in shaping the literary archetype of the sophisticated vampire before Bram Stoker’s Dracula. The ‘Year Without a Summer’ stands as a potent reminder of nature’s power and how extraordinary environmental events can, in unexpected ways, influence culture and creativity.

References and Further Reading.

For those eager to dive deeper into ‘The Year Without a Summer’, its historical impact, and its connection to the literary births at Villa Diodati, here are some recommended resources:

Websites:

‘Blast from the Past’, by Robert Evans. Smithsonian Magazine Website. July 2022.

The Year Without Summer: 1816, by Alex Bush. The Beehive, Massachusetts Historical Society. April 2020.

The year without a summer: Peering through volcanic veils, by Erik Conway, NASA website. October 2009.

Books:

Non-Fiction—

The Year Without Summer: 1816 and the Volcano That Darkened the World and Changed History, by William K Klingaman & Nicholas P Klingaman. 2014.

Shelley: The Pursuit, by Richard Holmes. 1974. A closer look at Percy Shelley, with significant sections on the 1816 summer.

Fiction—

The Year Without Summer: 1816 - One Event, Six Lives, a World Changed, by Guinevere Glasfurd. 2020.

Lord Byron's Novel: The Evening Land, by John Crowley. 2023.

Love, Sex & Frankenstein: A gothic feminist tale of Mary Shelley and the stormy summer that birthed a monstrous new literature, by Caroline Lea. 2023.

Academic Articles:

—Note that these articles are free to read on JSTOR with a free account.

Stommel, Henry and Elizabeth Stommel. ‘The Year Without a Summer’, Scientific American, vol. 240, no. 6 (1979): 176-186.

A foundational article on the climatic event.

Sachs, Jonathon. ‘1816: Romanticisms Quick and Slow’, Keats-Shelley Journal 66 (2017): 88–98.

Argues that 1816 was significant not just for its famous literary and political events but for the way it highlights the competing scales of time within the Romantic era.

If you’ve made it to the end of my rambling this week, thanks so much for reading! Again, if you haven’t read Byron’s ‘Darkness’, and you are a lover of horror and fantasy (—particularly apocalyptic texts), please click the poem title above and read it, it’s free! You won’t regret it.

Next Wednesday, I’m continuing the Short Story Dissections series with a deep dive into the Mary Shelley short story, ‘The Mortal Immortal’ (—sorry, I’m on a bit of a Romantic era kick).

I’m also currently researching the next Genre Genealogy Series instalment. We are going all Lovecraftian with Cosmic Horror next, so watch out for that in the coming weeks.

As usual, I hope you have a great weekend.

C M Reid at The Ink-Stained Desk.

Love this! Great write-up!